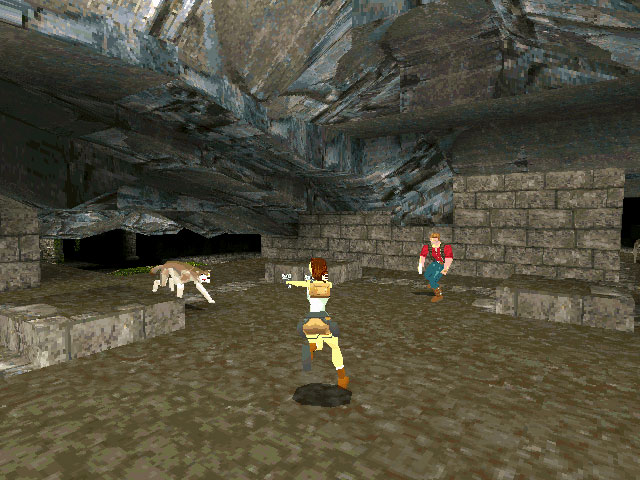

I feel almost embarrassed that I’m enjoying Rise of the Tomb Raider so much. This is the kind of overproduced, overly linear, overly prompted AAA shooter that sophisticated game commentators tend to disdain, but my sophistication as a game commentator can be measured in nanometers. I enjoy well-produced AAA games, even when they’re part of a series that began in the 1990s as masturbatory fantasies for 14-year-old Playstation owners who enjoyed watching Lara Croft’s ample curves trotting down the hallway ahead of them with a pair of guns in her shapely arms. Guns and curves: If it weren’t for those low-res Playstation graphics, the original Lara could have been a centerfold model for Gun Owners Monthly.

The newer Lara Croft is a lot higher resolution, though, and except for her uncanny ability to survive landslides on ice-covered landscapes (which usually requires a half dozen returns to the game’s last checkpoint for less agile tomb raiders like me), she could pass as a credible young woman just realizing that her life has a purpose beyond cramming for final exams and wondering when the hunkier archaeology nerds at Oxford were going to notice her subdued but undeniable attractiveness. This is a Lara Croft that young women can identify with and that young men might actually consider an intellectual equal rather than (purely) a sex object. (For some reason, though, she spends much of the game’s cut scenes hanging around with handsome older men, maybe because she has an almost Freudian obsession with her father, Tomb Raider, Sr., whose suicide over the rejection of his archaeological theories is something she blames herself for.)

In this post, though, I don’t want to talk about Lara so much as I want to talk about the tradition her character and her stories grew out of. And this tradition is not so much a gaming one as it is a literary and a cinematic one. It’s a tradition that in my case I learned to love at the age of five when my mother began reading me comic books about a feathered zillionaire named Scrooge McDuck. Yes, that Scrooge McDuck.

A Duck Tale

Most Americans not of my generation are probably familiar with Scrooge McDuck from the Disney Duck Tales animated TV series that began in the 1980s. But the avian mogul goes back a lot farther than that, to the comic books of the 1950s, and he was created by a man whose very name has an almost godlike resonance for me: Carl Barks.

For those who aren’t into older comic books (or who aren’t European; for some reason Barks has a much higher recognition factor in the hemisphere opposite the one where I’m sitting), Carl Barks was a Disney animator who produced Donald Duck cartoons in the 1930s, but his job as an animation artist never suited him. He wanted the creative freedom that self-employment would give him and in 1942 moved from creating Disney animation to creating Disney comic books.

It’s not surprising that he settled on the Disney ducks, Donald and his nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie, as his subjects, but the Donald of the comic books was a very different duck from his animated counterpart. He was no longer given to incoherent explosions of anger, but became more adventurous, not strong on initiative but encouraged by his nephews, who were members of the Boy-Scout-like Junior Woodchucks, to engage in exploration. Under Barks’ tutelage he would uncover pirate treasure and discover Viking ships encased in ice. But it wasn’t until Barks introduced Donald’s uncle Scrooge that the duck family’s wandering ways began taking them into the realm of genuine legend.

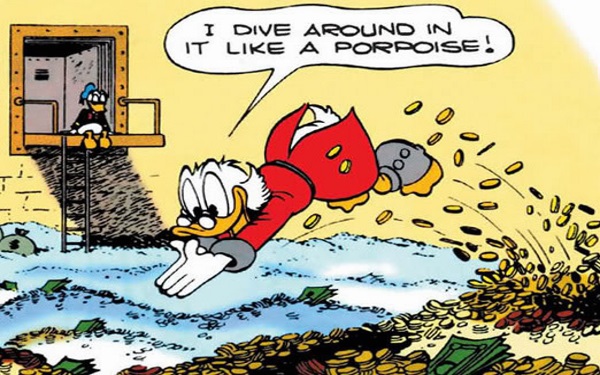

Scrooge first appeared in 1947 as a miserly old curmudgeon as dislikeable as his Dickensian namesake, but when he was given his own comic book in 1952 Barks turned him into something else entirely. He was still greedy and given to uncontrolled outbursts of anger not unlike those Donald was prone to in the cartoons, but he was also wistful for the adventures of his bygone youth, when he had been poor but ambitious, chopping firewood in the forests of his native Scotland and prospecting for gold in the wilds of the Yukon.

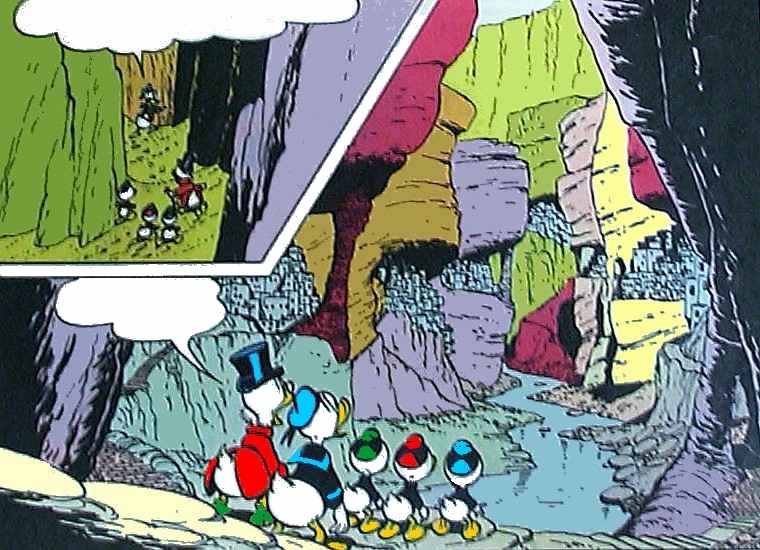

In later life he would be drawn into explorations, along with his relatives, that promised monetary gain but that turned out to be mythic in scope. He wanted to find the golden fleece sought by Jason and his Argonauts, but to find it had to negotiate the Greek island of Colchis, with its dragons and its larkies (the Disney version of harpies). He wanted to find the Philosopher’s Stone, which would transmute ordinary materials into gold, but ended up almost turning into gold himself. He wanted to find the fabled treasures of the Seven Cities of Cibola, but instead found an underground metroplex wired to trigger an ancient, horrible, spectacular trap.

Barks was actually working from an even older tradition, one started by novelist H. Rider Haggard, whose much-filmed 1885 bestseller King Solomon’s Mines launched a craze for stories of lost cities and lost civilizations buried in the last unexplored corners of the earth. It was a tradition that was later followed by Edgar Rice Burroughs in his Tarzan novels, where the archaeological genius raised by gorillas was constantly stumbling on the populated remains of bygone empires. Barks simply took Haggard’s hero Allan Quatermain and Burrough’s Tarzan and refashioned them as ducks, but they were such ingeniously conceived ducks that they brought a kind of wry yet thrilling humor to the Haggard-Burroughs sensibility that appealed to me immensely when I was five years old and still appeals to me today.

George Lucas and Stephen Spielberg also grew up with the Uncle Scrooge adventures and Indiana Jones is basically Donald Duck in Harrison Ford drag. (In the third film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Sean Connery essentially becomes his Uncle Scrooge.) And given that Lara Croft was quite consciously modeled on Indiana Jones she’s a linear descendant of Scrooge, Donald and the Haggard and Burroughs heroes who had preceded them. Lara, like Scrooge and Indy, is always in search of an artifact of ancient power. And like her predecessors she discovers lost cities and lost civilizations on her way to locating them. Rise of the Tomb Raider reminds me more of the Uncle Scrooge story “The Land of Tra-La-La” (the Barks version of James Hilton’s Shangri-La) than it does of any Indiana Jones stories. Both Scrooge and Lara stumble on peaceful societies of good shepherds living in nearly inaccessible mountain valleys, endangered by the encroaching forces of civilization and the greed that those forces represent.

I like the new Lara for many other reasons too, not just for her more realistic personality but for the meticulous graphics of her lost cities, which remind me of Barks’ work at its best. Compare these two images of Scrooge and Lara:

Lara’s stories are still basically linear, though there are large, explorable areas and multiple ways to get past some of the game’s obstacles. She still climbs walls of rock and falls off them a lot. But the Scrooge stories are, by their nature, even more linear and the thrill of discovery, heightened by the sense of learning that a piece of the ancient past is still alive, is always present in stories about both characters. In Rise of the Tomb Raider even more than in the previous reboot (or the earlier games) Lara finds herself treading the path that Allan Quatermain, Tarzan and Scrooge McDuck have trod before her. And I love both Lara and Scrooge for that magical voyage into living history as much, or more, than for anything else about them.

I love Scrooge, reminds me a lot of Richie Rich; well, money wise, that is. Once upon a time, I had a collection of comic books that also included some nice Mcduck issues. Those comics are gone now, replaced with more independents. But I’ve never forgotten them.

One such scrooge comic, told the story of some ancient Egyptians turning from dust to living and back to dust again. I found the comic on ebay at one time, but whoa I couldn’t see me shelling out what they wanted for it. I’m not an diehard collector, mind you.

Lara Croft, yeah, she is a looker (both game version and live action). I never quite could get the hang of the game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Tomb Raider games require a lot of patience. I’ve complained here and elsewhere that Lara seems to fall down and die a lot, which frustrated me so much that I never got into the series until they rebooted it. (I’m not sure if the games have gotten easier or if I’m just more motivated by the improved graphics and stories.

I had a very large collection of Scrooge comics when I was young, but over the years they vanished. I kept re-reading them even as an adult because Barks’ writing was so good, especially for comic books that were intended to be thrown away (usually by your parents) after you read them. Fifteen years ago I saw a large coffee-table edition of the stories that’s probably going for mega-bucks now, but maybe I should look around for a used copy.

LikeLike